|

Crime is on the rise in USA. Newer forms of crimes are popping up here. In fact America can be called the pioneer in modern day criminology. Normal sex has become outdated or rather out fashioned here. You date a girl and then have sex with her. So where is the "fillip"? Here is something new, which Americans are trying. Date a girl, drug her with something like a tranquilizer and then rape her. This is called Date Rape.

The glaring example of date rape is Mr. Andrew Luster. This gentleman from California has enjoyed sex this way 87 times so far. He used to serve GHB in juice for his would be victim. Mr. Luster used to record it on video and put it on the World Wide Web. He is one of the many playboy millionaires in USA. Arrested only recently because one of the victims thought it was a rather harsh way of enjoying sex.

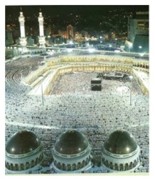

Courtesy: johnsomm@gdls.com The Last Namaz

The Rediff Special/ Ramesh Menon

Adversity has this strange knack of bringing people together. When you are battling for survival, caste and creed do not matter. Roving Editor Ramesh Menon details one such incident, which could have been a landmark in communally strife-torn Ahmedabad. Only, it was too good to last.

When the earth shook violently on January 26, the residents of Sarangpur Chakla -- like everyone else in Ahmedabad -- ran out of their homes. Many of them moved into the large courtyard of Rani's mosque, a 15th century monument. Located in an area that is dominated by Hindus, the mosque has been closed for over 32 years. But, as a protected heritage monument, it is being looked after by the Archaeological Survey of India.

It proved to be a safe shelter during the quake, since it is surrounded by an open area, while Sarangpur is dominated by narrow lanes and old buildings.

Soon after, a group of elderly Hindus approached Muslims in the Panchkuva area of Kalupur and asked them to begin offering namaz at the mosque again. They hoped it would please the Gods and the anger within the earth would subside. The Muslims happily acquiesced.

On January 31, a dozen-odd Muslims went to the mosque to offer namaz early in the morning. It was the first time since the 1969 communal riots in the city that this had happened.

The Hindus in the locality got together and organised water; before offering namaz, the Muslims are required to wash their hands and feet. "The residents thanked us and said our prayers would ward off danger to their area. Though the tremors continued, we thought it brought us together," remembers Mohsin Sheikh, a small-time businessman who deals with bags and plastic sheets.

For the next namaz, there were about two dozen Muslims offering prayers.

The one held in the afternoon saw four dozen devotees.

Though the numbers swelled to 250 for the namaz after sunset, the Muslims could sense the tension in the air. One of them walked up to a policeman outside the mosque and told him that, if there is a problem in them offering prayers there, they would stop immediately. The policeman said there was no problem; that the prayers -- which were for everyone's well-being -- should continue.

Yet, by the time of the night namaz, they were told not to come to the mosque, thanks to strident protests from a handful of vocal residents associated with the Vishwa Hindu Parishad, the Bajrang Dal and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

The residents themselves had no complaints about the namaz. The area's right wing elements, though, felt the presence of so many Muslims -- the numbers were increasing with each namaz -- should not be allowed since Sarangpur borders Muslim-dominated areas.

The last namaz of the day did not take place.

The amity between the two communities did not last 24 hours. Those who reached the mosque for the last namaz say the policemen were beginning to worry about communal tension and did not want anything to spark it.

Today, the iron gate leading to the mosque has been locked. The courtyard is silent except when the wind blows; then, one can hear the sound of rustling leaves.

Four policemen are sleeping in front of the gate; which is covered with their damp clothes. One of them views me with suspicion. "Have you come here to read namaz?" he demands.

I tell him I am, like him, a Hindu. Still suspicious, he says I cannot go in. "The mosque had been closed for years and will not open again. We are here to ensure that."

|

|